How to safely land a rocket on a floating drone

Space technologies are booming again. The latest development comes from Elon Musk's SpaceX.

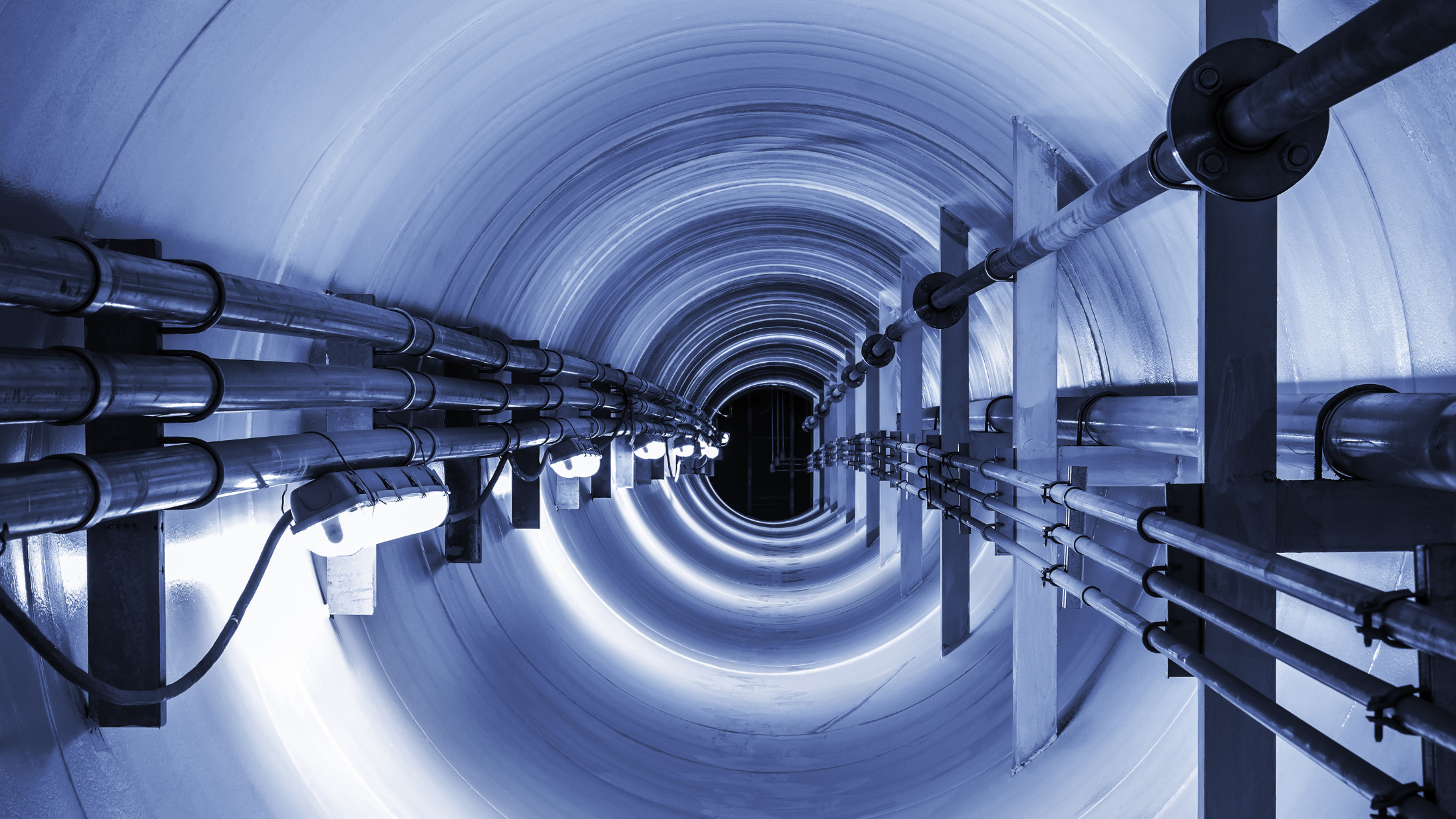

Check out part two of our three-part series on confined spaces and learn all about the classification and reclassification processes.

In the first part of this three-part series on confined spaces we introduced you to some of the grim statistics for confined spaces, talked about the numerous standards and provided two tools to help make understanding the standards a bit easier.

To further this discussion, part two will talk about specific terminology that OSHA uses in the standards which when not properly understood, can affect how spaces are classified. Along those lines, we’ll talk about the process for classifying spaces, how the reclassification process works and introduce several new templates and interactive tools created by EHS Insight that might help with the entire process.

Believe it or not, a fairly common confusion point for people working their way through the confined spaces standard is understanding what constitutes a confined space and understanding the different types of confined spaces. Many people become confused because they don’t look at the classification process as having two steps—but it really does.

The first step is simply deciding whether a space or area fits the criteria for being a confined space at all. This step in the process doesn’t include looking at hazards or talking about permits—that comes later. To make this determination, there are three criteria that all must be present within a space for that space to be considered a confined space:

The space must:

If a particular space doesn’t meet all three criteria, it’s not a confined space and doesn’t need further evaluation. However, if it does meet all three criteria, the space should be classified as a confined space and will require an additional classification step (which we’ll get to later).

At EHS Insight, we understood that while OSHA’s Confined Spaces Advisor tool works well and provides some very detailed guidance, being able to identify and document all potential confined spaces in one place is important. To help with that, we’ve created a tool to help you do just that. With our Confined Spaces Identification and Documentation tool, users can evaluate any space they think might be a confined space and by properly answering three simple questions they will be provided with a determination of whether the space is or is not an actual confined space. When a user has completed the process for each space in question, not only will they have a good working list of which spaces are and aren’t considered a confined space, but they will also have a record of the assessment should the classification of any of the spaces ever be questioned.

Now, let’s talk about terminology for a minute and look at an example of how a misinterpretation can change the way a space is classified.

While these three criteria for what constitutes a confined space may seem straightforward to some, to others it can be confusing because of how certain terminology is being interpreted. The terminology OSHA uses for deciding if a space is a confined space or not is important to understand because if it’s not interpreted properly, it can change how a space is classified. For example, the first criteria is that the space must be “Large enough and so configured that an employee can bodily enter and perform assigned work”—but what does it mean to “bodily enter” a space?

It’s easy to get confused because when looking at the other two criteria of having limited or restricted means for entry and exit and also not being designed for continuous human occupancy, this can lend itself to the idea that to “bodily enter” a space is referring to an employee’s whole body—but that’s incorrect. OSHA defines “bodily enter” as:

“The action by which a person passes through an opening into a permit-required confined space. Entry includes ensuing work activities in that space and is considered to have occurred as soon as any part of the entrant's body breaks the plane of an opening into the space.”

Here are two examples of how important this understanding is to the classification process and what can happen if it’s not interpreted as OSHA intended.

Scenario: A bin vent on top of a silo has an access door that allows for the filters inside to be changed out from time to time. This access door is fairly small and really only allows for an employee to place their hands, head and upper body inside to pull filters out and put new ones in. Based on the three criteria for classifying a confined space, how the employer interprets what it means to “bodily enter” a space is going to determine how the space is classified.

Example 1: If the employer considers “bodily entering” to mean an employee’s whole body, then based on the space’s configuration, the employer will not consider it a confined space—which is incorrect.

Example 2: If the employer considers “bodily entering” to mean when any part of an employee’s body breaks the plane of the space, the space will have met all three criteria and will therefore be properly classified as a confined space.

If you recall, in the introduction to this article, we talked about some of the grim safety statistics surrounding confined space fatalities and we posed a question essentially asking how the management of confined spaces can go so terribly wrong that it causes such incidents to occur. Misclassifying spaces because key terminology is misunderstood is one way that happens. The primary takeaway here is that terminology is really important and while OSHA may leave certain things up for interpretation, the terminology used in the classification of confined spaces is NOT one of those things!

Once the first part in the classification process has been completed and all the true confined spaces have been identified and documented, the next step is to individually evaluate each of those confined space to determine whether the space is going to require an entry permit or not.

For a confined space to require an entry permit, the space must include one or more of the following characteristics:

Here again understanding the key terminology used in this part of the process is important to ensuring the space is properly classified. Without a good understanding of what OSHA means by “potential” and “configuration” (among other things), spaces will end up being misclassified which has the potential to put lives at risk.

Because we know this part of the process can get a little tricky, we’ve created a Confined Spaces Hazard Evaluation tool to help users easily and quickly evaluate those spaces which they’ve already identified as “confined spaces” to determine which spaces will require a permit to enter. When the questions are answered properly, users will be left with a list of their confined spaces and a classification of each one as either a “permit-required” space or a “non-permit required” space.

Once this process has been completed, a facility will usually have a much better idea of how complex their confined spaces program will be. This is typically a good time to look at things from a 30,000 feet view and decide the feasibility of having the workforce performing permitted entries or not.

Many companies, especially smaller ones, will opt to hire a contractor to enter permit spaces rather than allowing their own workers to do so. On the surface this may sound like a big expense but it should be understood that no matter who is entering these spaces, whether it’s a contractor or a facility’s own employees—there’s going to be an expense either way. For a facility to comply with all the requirements included to enter a permit space, the costs can add up quickly, especially if that facility has to regularly enter these spaces. For example, to enter permit spaces requires initial and annual training for entrants, entry supervisors and attendants as well as training for rescuers. It also requires specialized equipment used for atmospheric testing and for rescue—and of course training how to use that equipment and upkeep on it. On top of this, there are always the time expenditures and labor costs associated with permit entries because every permit entry requires multiple people to participate for the duration of the entry—which can quickly become very costly and time consuming if permit spaces have to be routinely entered.

Performing a simple cost benefit analysis that compares the costs of using a contractor for permit entries to the costs of using a company’s own workforce can be a good exercise for a safety professional to do. Once again OSHA has devoted a segment of their website to understanding how to make the business case for safety which includes information on determining costs, benefits and provides resources for how to account for safety within the business, among other useful information.

Change happens in every facility and that change can affect the classification of confined spaces. Sometimes changes can unintentionally add new or additional hazards to a space and sometimes changes can eliminate hazards from a space—but either way, when changes take place that could or do affect a confined space, that space needs to be re-evaluated and possibly reclassified prior to the next entry. This activity is called the reclassification process and for many safety professionals, it’s the most frustrating, tedious part of managing a confined space program.

For non-permit required spaces that undergo a change that increases the hazards for entrants, the space must be re-evaluated and if necessary, reclassified as a permit-required space. When this happens, the space in question is given new signage, is added to the list of permit-required spaces and is entered the same way every other permit-required space is entered.

However, the process for reclassifying a permit-required space which has undergone changes to eliminate certain hazards is a bit more regulated.

For starters, a permit space may only be reclassified as a non-permit space when the space no longer poses either an actual or potential atmospheric hazard and when all the other hazards within the space have been eliminated—with a few caveats.

(It’s important to note that forced air ventilation does NOT constitute an elimination of atmospheric hazards.)

To make this process a bit easier, we’ve created a simple and editable Temporary Confined Space Reclassification template that guides users through the reclassification process and when completed, provides the necessary documentation to justify and certify that determination.

What’s Next?

Now that we’ve covered statistics, standards, the importance of understanding terminology, the initial classification process, the types of confined spaces and the reclassification process, the final part in our three part series on confined spaces will cover permits and post-entry activities. We will also introduce the final set of templates we’ve created to simplify managing not only the entry process itself but also the recommended follow up activities at the conclusion of an entry into a permit space and how to keep a good record of every entry.

Interested in seeing what other resources EHS Insight has to offer, please check out our website’s resource center and for those interested in hearing more about what our industry leading EHS software modules can do for you, please contact us!

Space technologies are booming again. The latest development comes from Elon Musk's SpaceX.

Working in confined spaces can be dangerous. Under regulation 29 CFR 1910.146, OSHA requires employees to be protected from hazards associated with...

Learn about what’s required to be in every confined space permit and how to keep the entire entry process organized.

Subscribe to our blog and receive updates on what’s new in the world of EHS, our software and other related topics.